"What’s in the box?"

From Yoko Ono's Smile, and Dark Matter's corridor of forking paths, to the time-travelling coffins of Primer, the box as liminal device

It was a black wooden oblong, with carved lettering rising out of the lid. Hinged at the back, the letters read simply, ‘Smile’. Raising the lid to open the box towards yourself with one hand, instinctively, with the other, you tilt the bottom slightly, moving the closer edge away and down, so you can peer inside. Shining right back at you bright and perfectly framed by the black painted insides of the box, a mouth, your mouth, reflected in a mirror, breaking into a smile.

I was in the living room of Richard Metzger, circa late-August 2004, almost 20 years ago — a short cameo of the Disinformation and Dangerous Minds founder, who you’ll hear more about here in the coming days. We were there to see his art collection. That Smile box, a Yoko Ono piece, has been a model for a pure, simple idea of art ever since. Art as play. Without pretext or pretence, the called for smile, provokes a joyful recognition and playful call and response. It’s a smile, it’s your smile. A kind of perfect gift.

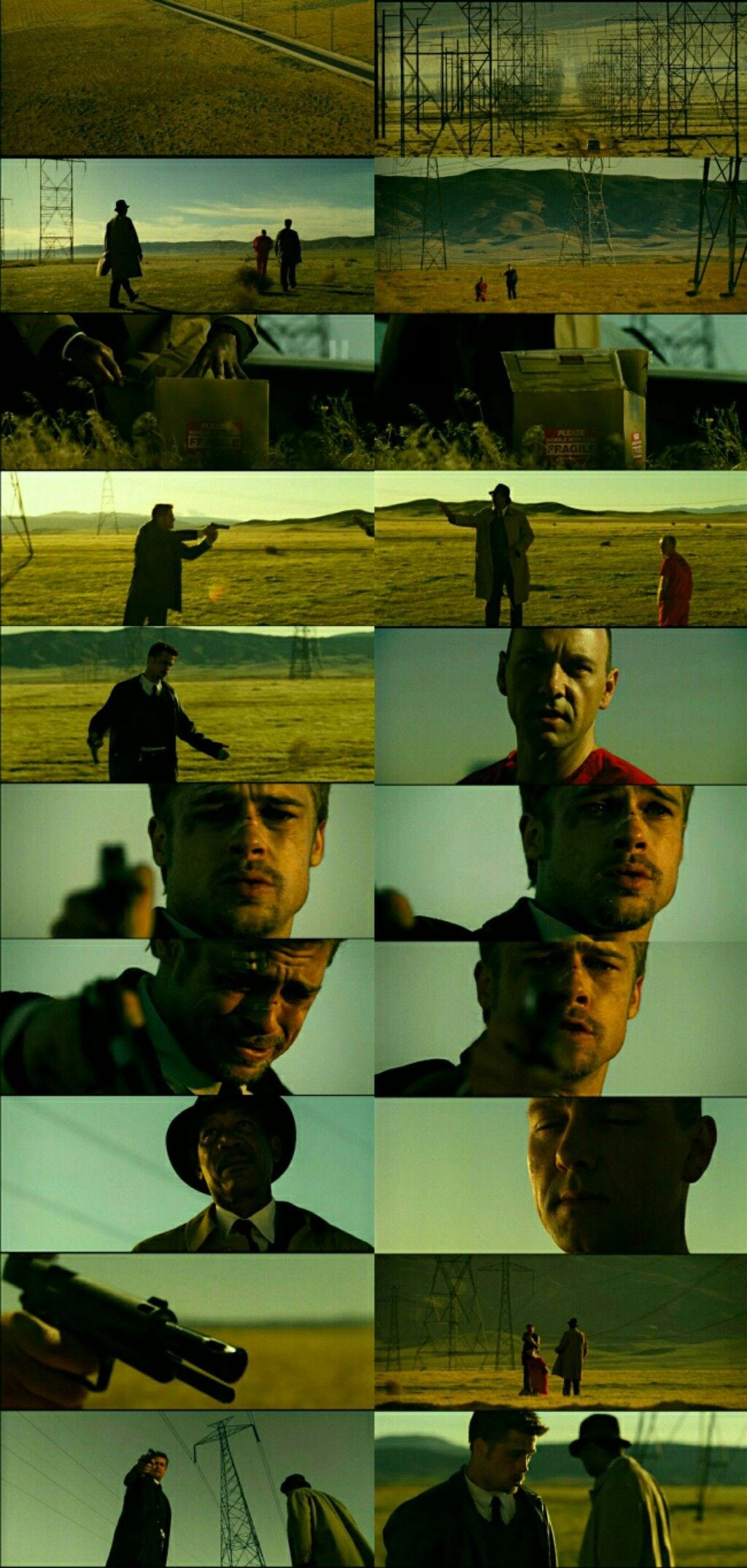

I’ve been thinking of boxes a lot recently. Boxes as spaces, as enclosed space, like little parcels of reality that can be closed off, separated, put away for storage, and what this means. How the box functions, especially metaphorically, in myth, literature, film, and culture, as mysterious, even secretive, places of hiding, as liminal, where the rules may change inside, as portals or points of transformation. From pandora’s box of evils, to the lamentation configurations of La Marchand’s puzzle boxes in Hellraiser, Marsellus Wallace’s golden glow briefcase McGuffin in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, or the Fed-Ex please handle with care box delivering the culmination of John Doe’s (Kevin Spacey) monstrous cycle of sins in Se7en. “What’s in the box?”, extorts the increasingly desperate Mills, played by Brad Pitt, to Morgan Freeman’s Detective Somerset.

[What’s in a box?]

The line hit me watching the recent Apple TV series Dark Matter. Based on a book of the same name by Blake Crouch, the show follows local physics professor Jason Dessen (J2) — played by Joel Edgerton, a favourite, see Paul Schrader’s excellent Master Gardener or Thomas M. Wright’s The Stranger. Jason (J2) is accosted late at night, knocked out and wakes up in world in which Jason Dessen (J1) is a rich and famous scientist, has won multiple awards, and who has been missing for months.

The morality tale set up here is a kind of alternative timelines Trading Places, if complicated by the infinite iterations of its sci-fi set up. J1 and J2 are split by a single choice fifteen years or so earlier. This new Jason never married our protagonist’s (J2) wife Daniela, and thus their son Charlie was never born. J1 chose science and his work, achieving breakthroughs and acclaim; J2 chose Daniela and love, leading a simpler family life. They each have what the other ostensibly wants, what the other lacks.

Dedicated to science, J1 took the idea of the box from the Schrödinger's cat thought experiment and built it out into a huge concrete-lined cube which functions as a gateway into parallel worlds. Haunted by the idea of the life he could have had if he’d only chosen Daniela instead of his work, by the road not taken, he then stumbles upon that life through exploring the worlds the the box makes available to him, and conspires to take it and the world of J2 for himself.

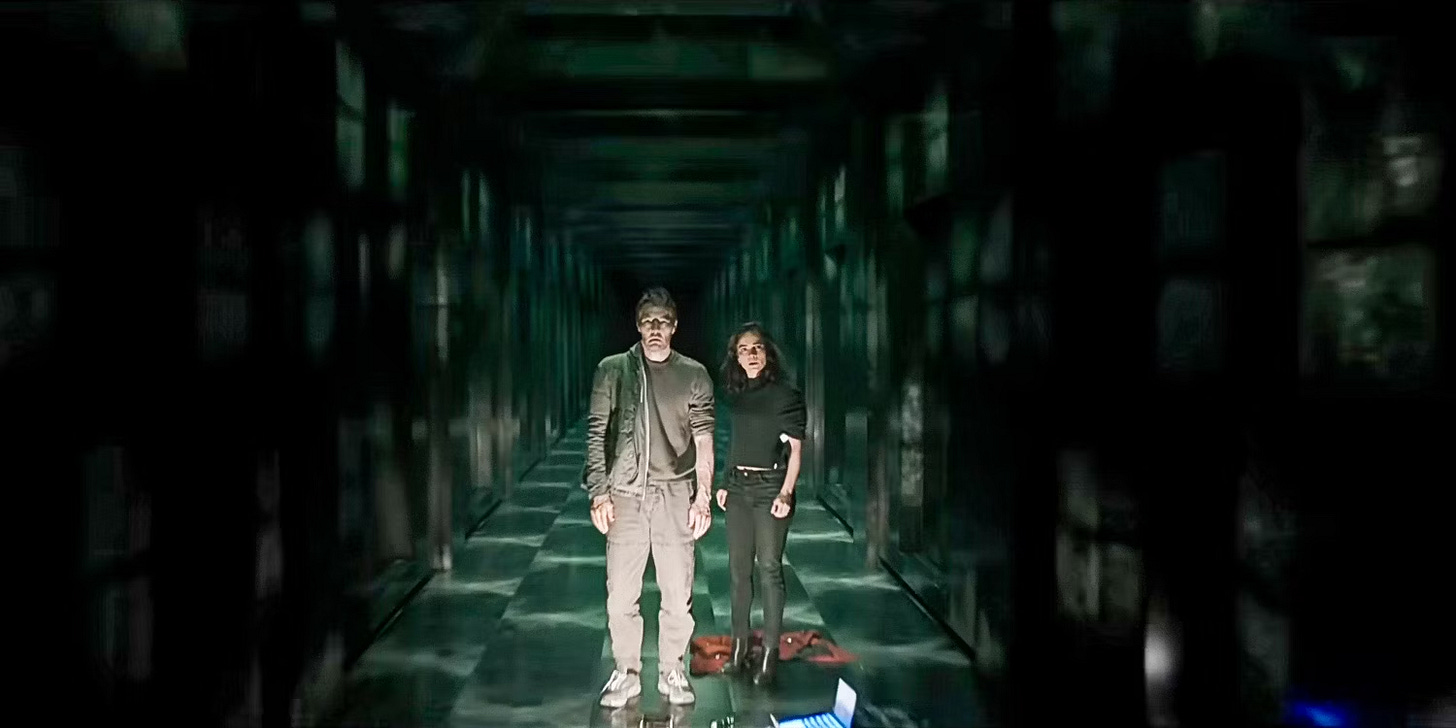

Desperate to get back to his wife and son, to the life he has been wrenched out of, the abducted and abandoned J2 instinctively rejects J1’s life of scientific success —morally suggesting that he made the right choice all along, that love trumps all— and flees into the box his alternate self built, accompanied by J1’s lover-therapist Amanda (A2). Cue reality-hopping adventures as the pair search this multiverse of alternative worlds and the different lives they each could have lived in search of J1’s home — or at least one indistinguishable close to it.

When they step into the box, it’s simply a hollow concrete cube. Closing the door cuts them off from the world outside, effectively putting them into a state of quantum superposition. This is revealed to them after they inject a novel psychoactive compound, that suppresses some world-constructing function of the brain. The walls beside them disappear as the box becomes an endless corridor lined with doors that recedes infinitely into a vanishing point on either side.

As J1 explains it to his friend Ryan Holder (H2) in episode 6 ‘Superposition’, having lured him into the box:

H2: I don’t understand what I’m seeing

J1: Well, this is a manifestation of your mind as it tries to visually explain something our brains haven’t evolved to comprehend.

H2: Which is what?

J1: A five-dimensional probability space, also known as superposition.

H2: Jay… are you saying I’m in a quantum state right now?

J1: Yeah. Yeah

H2: Jay.

J1: Now, it looks like a corridor, but it’s actually the box repeating itself across all possible realities that share the same coordinates of space and time.

H2: This can’t be… This is real. Jay? What’s behind the doors?

J1: An infinite amount of variations of the world you know. Some subtly different and some that’ll blow your fucking mind.

H2: Fuck

J1: Wait. Wait no.

H2: What?

J1: This… Okay this is the dangerous part. Aspects of your consciousness, like your emotional state determine which reality we find when we open a door.

The Schrödinger's cat thought experiment goes as follows: a live cat is placed in a box, together with a vial of poison controlled by a radioactive substance. The box is sealed, so we do not know what is happening inside. Once the radioactive isotope decays, at some random and indefinable point, it would trigger the poison, thus killing the cat. But, without opening the box we (the observer on the outside) cannot know if the cat is alive or dead — if the random event of the isotope decay (that may or may not happen) has occurred to release the poison and kill the cat. Thus, unobserved, the cat must be considered to be in two different states at once, it is simultaneously both alive and dead.

The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics explains that a quantum system exists in all of its possible states at the same time. We only confirm the true state of the system when we make an observation of it. When we look in the box, we can see that the cat is either alive or dead, not both at the same time. At what point does this quantum superposition end, and reality resolve itself into one possibility or the other?

[Inverting Schrödinger's cat]

What Crouch does in Dark Matter is use his box to invert the thought experiment. Rather than the question of whether the cat is alive or dead in the box — it’s both, until we can open the box and verify it with observation — in Dark Matter, it’s the observer who is put in the box, the observer becomes the sequestered cat, and it is the world outside that becomes suspended through the revealed superposition or quantum indeterminacy. A relativistic retelling of the thought experiment from the point of view of the cat. It’s only when we open the door that we can verify which of the infinite possible worlds is on the other side.

Entering the state of superposition is re-presented and narratively framed to us through the metamorphosis of the box itself. It becomes a corridor infinitely echoing the internal spatial dimensions of the box. This corridor of echoes is a liminal space, but not a linear space. The doors next to each other are not worlds one step removed, one small choice away. Rather the apparent linearity of the corridor is an illusion, a function of the mind, and a function of the narrative re-presentation of the concept of superposition — i.e. a narrative device to communicate to the audience the idea of parallel worlds linked by this liminal / other space of the corridor.

There is only the one box, however. And, one might think that, to actually start running along the ‘corridor’ would mean after a stride or two your physical body would smack into the wall. Thus, any actually attempted movement along the corridor would likewise be a purely mental construct of the protagonists themselves. In this sense, the process of choosing a door, of flitting between the superpositional states and the respective worlds we would find on the other side of those door, would perhaps be better represented by a corridor that itself moved (perhaps rotating on a wheel like a giant roulette table, or sliding past like the famous ‘construct’ scene where weapon racks blur past Neo and Trinity in The Matrix), with our observers, our characters, fixed in place. With an infinite array of possibilities spinning past this could rapidly become a meaningless blur.

The corridor is a narrative device, helping us to grasp the concept of superposition, as an audience, and providing a pathway for the characters to transition between worlds. How the world behind the door is determined in Crouch’s Dark Matter is emotionally, intentionally, and largely unconsciously. There is only the one box, and thus only the one door. Which world it opens into is ‘picked’ by the state of the person who opens it, which of the infinite states of quantum position they are in that they take to it. Thus fear leads to worlds on fire or submerged in ice or water, loss to ones full of grief, for example. For all the science of the set up, ultimately our characters manifest the worlds they encounter.

Another aspect of Crouch’s reality-hopping mis-en-scene, is that in Dark Matter, the set of infinite possible worlds accessible through the box is inherently constrained to those consistent with the arrangement of atoms of our observers (loosely defined enough to enable a consistency of narration) — as J1 says, ‘all possible realities that share the same coordinates of space and time’. This serves to rule out worlds where a minutely slowed galactic rotation speed, for example, would place the box 20ft underground, or in the midst of the Earth’s molten core, or floating in space in the wake of the planet’s own orbit around the sun — as if the idea of spatial coordinates objectively existing across multiple super-positional worlds made sense.

More importantly, this is also temporal. In all these possible worlds, time passes the same. An hour in J1’s world (W1) is the same as in J2’s (W2). Whatever choices have bifurcated these realities, the same amount of time, of durance, separates them from that split, the equivalent characters in each have aged the same. We have garden of forking paths, with each world’s distinct timeline progressing to a universal and fixed pace. As such, there is no relativity between worlds in terms of space / time — at least in terms of the set demarcated by those accessible through the box.

What interests and excites me here, is what this leaves out by omission as much as what it includes. In presenting the co-ordinating axis of ‘a fifth-dimensional probability space’ — simply put as three spatial dimension, time, and then a dimension of infinitely compresent variations of the possible permutations of the stuff in those three spatial dimensions, how they are arranged in space, and the paths by which they got there through time — what does this reveal about the limits of our ability to think and to narratively re-present, i.e. tell stories within and through, these higher dimensional constructs? What, if anything, does this reveal about ourselves, or the world as we re-present it to ourselves? Dark Matter uses the box as a liminal space to move between alternative realities that are, in a sense, side by side — in that ‘fifth-dimensional probability space’.

[Prime Time]

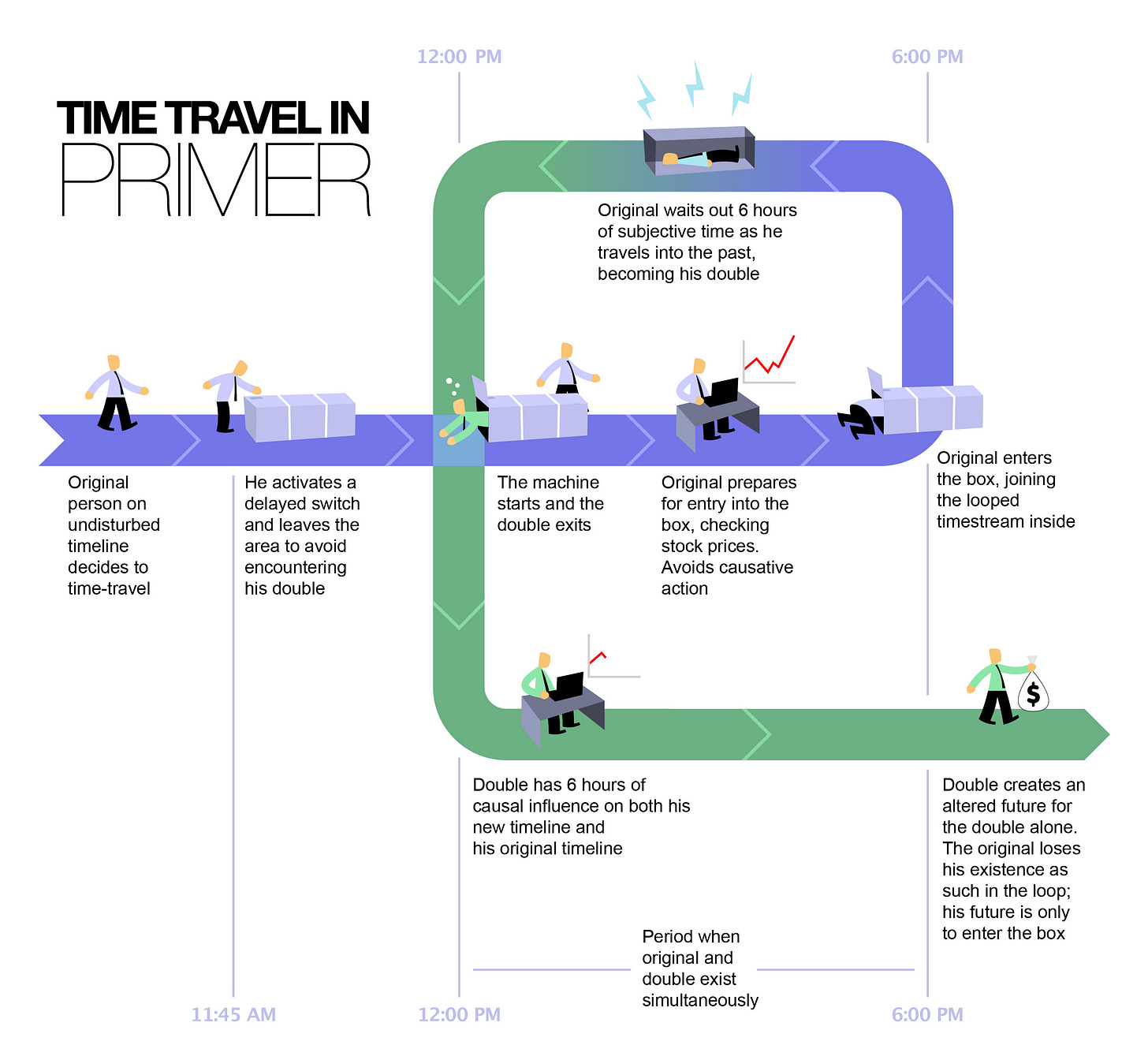

Described by Looper director Rian Johnson as ‘the perfect time travel movie’, Shane Carruth’s 2004 film Primer is a masterpiece of low budget, independent sci-fi. It’s use of the box is an almost perfect parallel to Dark Matter, but instead of moving sideways between multiple existent alternative realities, Primer loops us back on a single-reel tape of time. In it two struggling entrepreneur-inventors Abe and Aaron, working away in their garage, accidentally make themselves a time machine. Although what they originally think it’s for or should do is never revealed, the pair build a metal box that has unexpected qualities. When it’s switched on, time passes differently for objects put inside — a patina of protein goo secreted by a fungus, that would take 5 years to accrue naturally, appears on a watch in 5 days. Even unplugged from the batteries, the machine keeps going, its humming slowly fading as it cycles down. Abe realises something is up, builds a larger, human sized box, tests it and then reveals the startling discovery to Aaron — in one of the sparse film’s subtly echoing scenes and stutters. The box allows them to travel back in time.

The pair cautiously set some ground rules to avoid causality paradoxes. Before going in the box, they spend the day in a hotel room, hiding out, not interfering with the world, allowing their doubles from the future, their future-selves, to live that time. After switching on the machine in the morning and hiding out in the hotel (making a note of the day’s big movers on the stock market), that evening they make their way to the storage unit hosting the boxes, switch them off, get in as the machine cycles down and they travel back to that morning to relive the day again. This time armed with the knowledge of which trades to make — their daily version of Biff’s Grays Sports Almanac 1950-2050 from Back to the Future Part II.

From that initial proof of concept, Abe and Aaron get increasingly confident, looping back more and more, getting sloppy with their quarantine. They leave the hotel for a snack. Aaron keeps his phone on him and it rings — as the phones are on a network, if the call finds his phone it doesn’t ring for his duplicate, breaking the symmetry and introducing drift or interference into their personal timelines. They start talking about deliberately un-syncing themselves, looping back over themselves and erasing their own earlier selves, pursuing a beef with a boss at work and then ducking the consequences by erasing that sequence of events.

[For anyone interested in a detailed trace of the various time travel trips and loops in Primer this is perhaps the best]

In Primer, we have one timeline, one world. There isn’t a bifurcation into distinct realities (at least as re-presented in the film). All events later in the film, are already present at the start, and yet paradoxes and blunt ends emerge, as that timeline loops and gyres around itself. The box, or coffin as they are described, is not a space one moves through, per se, but rather one that the traveller persists in, they endure. While the coffin reference suggests a space of death, of un-life perhaps, that our travellers pass through — as such the myths of Orpheus and Persephone might be interesting to consider here, Cocteau’s Orphée, or even Alice Rohrwacher’s La chimera — they describe it as a womb-life experience, the machine hums, they’re hooked up to oxygen tanks to breathe, take dramamine to sleep inside, and have a feel of deep contentment. Aaron notes how different it is in there, “You can feel how cut off you are, you know. It’s this entirely separate world and you encompass most of it.” “And the sound,” Abe counters, “Isn’t the sound different on the inside? it’s like it’s singing.” Inside, Aaron dreams, of the ocean, of waves…

From the point of view of our observers, switching the box on creates an anchor, the earliest point in time at which one could go back to through it. The box becomes a space of liminal time, of time experienced and passed outside of or independent to the time passing in the world beyond. At any point after the box is on, our protagonists could switch it off, get in and ‘ride it’ back to that anchor point. Quite what would happen if you spent longer in the box than it has been turned on for, is left mute. Much as the paradox or mystery ensuing by switching it off when someone is presumably inside, etc. Or of opening it and looking inside — is there a body inside? Or re-using a box that is already in use. Or even putting a box, in use, inside another larger box. Primer merely hints tantalisingly at these suggestions of higher order complexities. The film’s end hints at Aaron or one of his doubles building of a room-sized box, one with space not simply to endure, like a living-corpse, but space enough to live in. The coffin’s enigma becoming, perhaps metastasising into, a kind of parasitical liminal space, liminal time.

At one point they encounter another character, an old man they had courted for investment. He has days of stubble growth, and collapses into a coma. It’s a duplicate — his present self safely at home. He has looped back from the future using one of their boxes. How does that happen? Is the coma due to a complication with the oxygen in the box, or is he a causal loose end, a dangler of the causal pathway of events that led him here, some kind of soul tether shorn reducing him to a body without agency? In shock at this turn of events, Abe goes back to a failsafe device he had set up after his first test loop and has left running since. A box he could use to reset the timeline, go back to that first morning where he revealed the box to Aaron.

Primer is a film of takes, repeats, subtle echoes. It asks us how many turns of the circle, loops of the gyre, would it take to get it right? Made on a shoestring, the film itself was edited with barely a shot or frame left on the cutting room floor. This amplifies the sparsity of the filmic world. Abe’s reset takes him back to an earlier scene, he’s on a roof looking down at Aaron sat on a bench in the middle of a sunlit square. But which Abe is one the roof, the original or the double? Is this a new scene than before, or is this the exact same one repeating. In going back Abe has intercepted and presumably abducted his younger self, to replace him — throughout the film there are strange noises in the attic, racoons or a double tied up and gagged?

[The double as doppelgänger]

Abe collapses on the floor. On the earpiece Aaron is wearing you can hear the conversation from first time round playing. Again, as Aaron goes over to Abe the shot stutters, we see the same move a couple of times, echoes, repeating cycles. Aaron clocked the second storage unit with Abe’s failsafe device in it on the storage manifest. With the modular design of the coffins, he folded one up, and put it inside another. “They are not one-time use only. They are recyclable”. He went back with Abe’s failsafe, set up his own. Recorded the audio of events over those days, and then went back and replayed them, listening to the cues via his earpiece all along. A three second head-start. Even then this double is out of sync. Conversations drift subtly off script, his misses a basketball shot he made at the time of his recording, the map is not the territory, difference is at the heart of the loop.

From this Gordian Knot of temporal loops and doubles on, Primer’s narrative orbits a confrontation at a party. Aaron has been looping back, replaying and re-enacting these days leading up to the event. A voice over at the end, Aaron’s voice, asks us how many attempts it took to perfect this moment? In their descriptions of what is meant to happen, it’s not really a big thing. The event happens off camera, it is un-represented to us, perhaps lost in its repetition and replaying. A minor fracas at a party, someone’s ex pulls a guy. Perhaps nothing happened the first time around. Then Aaron, trying to be a hero, wanting to tweak it, interfered and maybe caused something terrible, kick starting a spiralling attempt to fix it, an exhaustive looping palimpsest replay of these few days desperately trying to claw its way back to the beginning, to an untrammelled state, until at the end all we see are the smudges lingering on the edge of the xerox and staining a halo of fatigue into Aaron’s eyes.

In this sense you could think of Primer as a time travel film in which nothing happens. An event that accelerated its spiralling is erased and overwritten by subsequent loops, until we have no record left of it, simply intimations in the uncertain minds and un-corroborating memories of our protagonists and their doubles.

“…what the world remembers, the actuality, the last revision, is what counts apparently. So how many times did it take Aaron, as he cycled through the same conversations lip-synching trivia over and over? How many times would it take before he got it right? Three? Four? Twenty? I decided to believe that only one more would have done it. I can almost sleep at night if there’s only one more...”

— Aaron (played by director-writer Shane Carruth) in V.O. at the end of Primer.

There’s an interesting moral asymmetry in the conclusions of Dark Matter and Primer, between the doubles and ‘originals’, between those left behind to live their lives untouched by ‘the box’ and those venturing ever on into new worlds or new temporal iterations. That’s a case for another time. Nevertheless, in many ways I see these films as partners, or siblings. Each uses the box as a narrative metaphor for transformative travel between alternative realities and/or timelines. Dark Matter spatially; Primer temporally. I am left with the question, between the corridor and coffin, of how these representations expand our understanding of higher dimensional constructs?