Writing After the End — 1/4

From the archive: Contemplating the contemporary through a caffeine riddle, reading Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island at Venice's All the World’s Futures [2015]

As promised in the de Duve post back in January, my ‘Writing After the End of Writing’ feature on Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island, published in Mihda Koray’s Near East magazine back in 2015. Eerily contemporary for a dip in the archive, there’s a timeless feel to the accounts of the Venice Biennale, new video streaming apps and Tom’s vision of parachutes let loose to the winds.

I’ve split this into four bite sized posts, partly as the text lends itself to it, but also to experiment with serialisation. Something under-explored on this app I feel, so please do share your thoughts. Enjoy!

**

“W., Is that you?” he asked, peering over dipped shades in the garden of Palazzetto Bru Zane in San Polo, Venice. Wearing a trim, dark linen suit, standard issue sunglasses, and hair tightly cropped, the author had just completed a reading of his latest novel in one of the upstairs halls. Pinching the neck of a champagne flute in one hand, his eyes darted once, searching for an answer. As we loitered momentarily in between the celebrated curator and magazine editor with whom he had just shared a stage, it struck me that there had always been something of the secret agent about Tom McCarthy.

I was in Venice for the biennale. Arriving a few days before the press circus kicked into gear and staying in St Elena at the southeastern tip of the islands, offered a calm sleepy neighbourhood, quiet like a mountain village, vacant of tourists and the bustling hustles of the alleys and canals. Each morning, after sipping uno espresso at the counter of a local bar, I would sit on one of Cafe Paradiso's little tables outside the entrance to the Giardini watching the water buses off-load their passengers, gazing out over the waters from the bank of the lagoon, reading my former supervisor’s new novel.

McCarthy’s Satin Island is the story of U., a corporate anthropologist working for the Company, a nameless agency dealing in ‘narratives'. U.’s work involves providing strategic advice for brands like Levi Strauss jeans, often by taking avant-garde leftist theory (Lévi-Strauss, Deleuze) and plugging it back into the capitalist machine. Beyond this, U.’s charismatic boss Peyman (a kind of bloated cross between Rem Koolhaus and William Gibson’s Hubertus Bigend) charges him with writing the 'Great Report' — a definitive account of the contemporary, as part of a much larger invisible project that will apparently 'change everything'. Heroic, modernist stuff for sure. Except that without a set brief to work towards, U. never gets round to writing the great report itself. With a subject as ubiquitous as 'the now', U.’s ongoing research covers everything and nothing. He compiles scrappy dossiers of illegible notes into topics as varied as oil spills, parachute deaths, south pacific cargo cults and buffering. But, like a Thomas Barnhard novel, we never get to read this Platonic great report. Instead, Satin Island is filled with everything else, with U.’s account of not-writing it and by the detritus thrown off by that process.

It is easy to identify with a character called U., every sentence can feel like it is personally directed. Indeed, McCarthy’s Kafkaian protagonist is a modern day everyman. Almost everyone I know who has read the book identifies strongly with him. “U. could be me,” is a common reply, “that’s my job he’s describing!” I remember thinking that, perhaps McCarthy’s compromised corporate anthropologist has captured something, a pervading feeling of futility: a sense that no matter how well educated and informed and inspired and passionate we are about our causes, the magnum opus we each work towards today is always already out of reach. The thought carried me to the idea that most architects failing to break through professionally are probably condemned to working on the mundane, traffic islands or stop signals even. It carried me to Roarke-ish individualists crafting detailed plans and blueprints for unrealizable projects, great arching mausoleums like the French C18th visionary Boullée. That perhaps we’re all collectively carving out grand cenotaphs never to be built. Sat soaking in the mid-morning sun, by the lagoon, buzzing under a riddle of caffeine shots, Satin Island felt like a book about the contemporary, somehow uniquely capturing the modern condition. What subjectivity is today. What it all means.

The vaporettos spit out more art world insiders, faces and names, steely associate directors and flamboyant Latin collectors. A large poster on the terminal billows lightly in the breeze kicking up off the waters. All The World’s Futures — the title and theme the biennale writ in large bright red lettering. It is a Baroque curatorial approach, taking a single theme split into three strands, with yet more sub-threads dangling loosely beneath them, that ultimately fails to provide a frame of reference. With it impossible to place more than a handful of artworks successfully in this semantic architecture, the biennale comes across like a grand menagerie of unique pieces, objects and words shorn of all context to sit lost and adrift.

The challenge with the world’s largest group show, of course, is both its scale and that of its audience. The biennale is implicitly about making an artistic statement to the world. But this begs the question of how effective communication with the global multitudes, across cultures, across generations, across languages, is even possible?

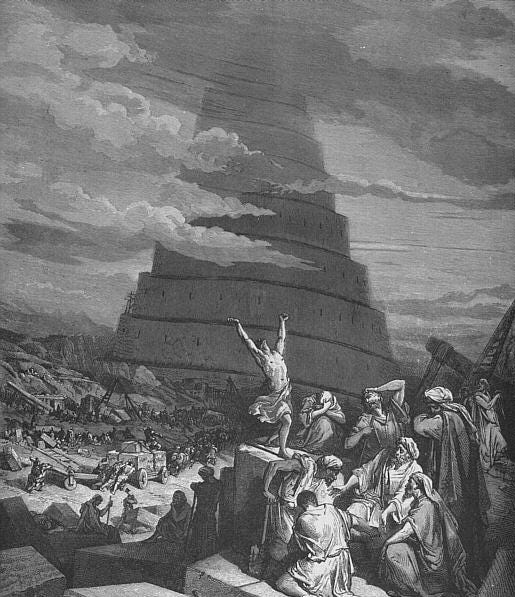

Fittingly, the logo for U.’s Company in Satin Island is a giant, crumbling tower. Babel. Channeling Koolhaus, the part-Persian Peyman claims the myth has been misunderstood. Rather than a symbol of man’s hubris, the attempt to reach the heavens through the tower and speak the language of God only matters in its failure. The collapse that scatters the tower’s would-be occupants horizontally across the earth, babbling away in different tongues, actually becomes "the precondition for all subsequent exchange, all cultural activity”. That the jagged ruins and rusty scaffolding remain derelict and useless is actually what is most valuable about them. This uselessness sets the ruins to work as a spur to the imagination and productiveness. And thus, any strategy of cultural production must first liberate things into uselessness. Perhaps then, I wondered, are the biennale’s failures deliberate and liberating, like being gifted a handful of jigsaw pieces without a puzzle?

I only hear about McCarthy's talk in Venice a day beforehand, in a moment of deliberately distracted and self-induced boredom scanning the events listings on Facebook for other things going on. #FOMO. In the bright early morning I rode the vaporetto back up the grand canal, into the heart of the city of light. Watching gondoliers set up their boats and the crooked shadow of an old woman, almost bent double by the weight of her black shawl, stand palm out, upward facing, begging for alms in a lonely corner, I sat for an hour in a local square, burning through the final few chapters of the novel's climax.

During the reading, McCarthy's voice rang out like on the tannoy at a local train station. Each word was carefully enunciated, revealing new alliterations, subtle rhymes and unconscious resonances that had been lost in my own reading of the text. Like a Sartrean waiter, he was almost playing, playing at the precision and care in delivery of public service announcements, playing so that all meaning and mis-meaning might linger out in the air between us all like forgotten children left behind on an evacuated platform.

Stepping outside into the mid-morning sun, shuffling through the pleasantries of another reception and sipping sparkling water, I nod.

“Yes T., it’s me. W.”