Writing After the End — 4/4

From the archive: Hanging air time over the chasm, labyrinthine networks of power, and the technology of writing, in Tom McCarthy's Satin Island.

Parachutes let slip their charge, erotically bankrupt future sex acts and agents waiting to be recalled in part four from ‘Writing After the End of Writing’, originally published in Near East magazine in 2015.

Lamplight skipped scattered arpeggios across the silken black surface of the lagoon. Walking back along Venice's long waterfront through the silent night, I think back to the biennale’s title. All the World’s Futures. It suggests that this one moment, one point in time, was the fulcrum and axis about which all else turned. It names this moment. That from now, everything is defined, chosen, limited, excised, forgiven, forgotten, born and lost, as if to pass away into a dream. It’s a conceit and a truism of course — all potential and possibility lies hollowingly within the actual. This moment could be any other. It is every other. But to name it, focus it, draw our collective attention down and together — if but for the sheer popularity and visibility of the biennale itself — perhaps makes of it something? Even if but for a choice, a call for a choice, for action.

Another of Peyman’s riffs in Satin Island is about knowledge: that the last individual enjoying a full command of the intellectual activity of their day, was Leibniz. The C17th polymath was on top of it all, physics, chemistry, geology, philosophy, maths, engineering, medicine, theology, aesthetics, politics. But since then the disciplines have scattered like the would be residents of Babel. “Each in its own stall, shut off from all the others.” A Leibniz 2.0 is now impossible; no single human intellect is capable of unifying this diaspora across the fields of knowledge. Instead, Peyman see continual migration and mutation. Each discipline surpassing itself and breaking its own boundaries, merging with each other into new fantastical mirages upon impossible topologies in the interstitial zones between what can be known.

Reading a newspaper, U.’s attention gets caught by the story of a parachutist who died when his chute failed on a jump. The death is being treated as a murder case and U. becomes obsessed. Consumed, he devours all the details, researches other examples and similar cases, concocts elaborate whodunits and proofs of dark suicide cult conspiracies. Rather than the fate of the man, the most striking image comes when McCarthy writes of the parachute let slip of its charge, billowing freely in the skies above as the jumper plummets in terror to be dashed on the ground below.

8.1 And all this time, behind these apparitions, another one: the image of a severed parachute that floated, like some jellyfish or octopus, through the polluted waters of my mind: the domed canopy above, the floppy strings casually twinning their way downwards from this like blithe tentacles, free ends waving in the breeze… This sense of calm, of languidness, grows all the more pronounced when set against the pain of the man hurtling away from it below. He would have looked up, naturally, and seen the chute lolling unburdened and indifferent above him—as though freed from the dense load of all its troubles, that conglomeration of anxiety and nerves that he, and the human form in general, represented.

— Satin Island, p.77

This air-born jellyfish took me back to Benjamin's angel of history, forever facing the past with its wings caught in the winds roaring out of creation and its back forever to the future.

As time and information swells and roars around us, as our comprehension of the present moment shrinks in focus and the sum total of all knowledge surpasses the capabilities of the knower, are we now not left behind as lost to the world and doomed as the falling jumper? Already dead, in some kind of half-life free-fall, like Wile E. Coyote hanging air time above the chasm. An angel shorn of its wings, cast out of history as residual and collateral to the surge and roars of the great storm of the world. Exit stage left.

Back in the small garden, on a patchwork of little islands clustered in the waters of the Adriatic, I ask T. if this is what the jellyfish represents. With our technologies now increasingly autonomous, are we no longer the protagonists in the story of the world? Is this the moment U. writes about, in negative, in his reports? Writes without writing?

McCarthy smiles. Behind the shades, I wonder if there’s that knowing glint.

The deferred climax of Satin Island sees U.’s girlfriend Madison recount her experience as a protestor at anti-capitalist riots in Genoa. Brutally herded up by militarized police corps, shuttled to a school gymnasium and beaten, Madison is then taken alone to a remote Alpine villa. In a decidedly Lynchian setting, Madison is made to perform an algorithmic sequence of bizarre nonsensical yoga-esque poses by a portly suit-wearing Euro-crat executive waving a cattle-prod, like some erotically bankrupt future sex act.

The episode sits in the book as both a promise of meaning and its renunciation at the same time. Fundamentally meaningless, or rather beyond meaning, laden with a profound, inscrutable and indecipherable truth that goes beyond its telling, it is the point the text comes closest to revealing everything but…

“[It reveals] nothing.”

Exactly.

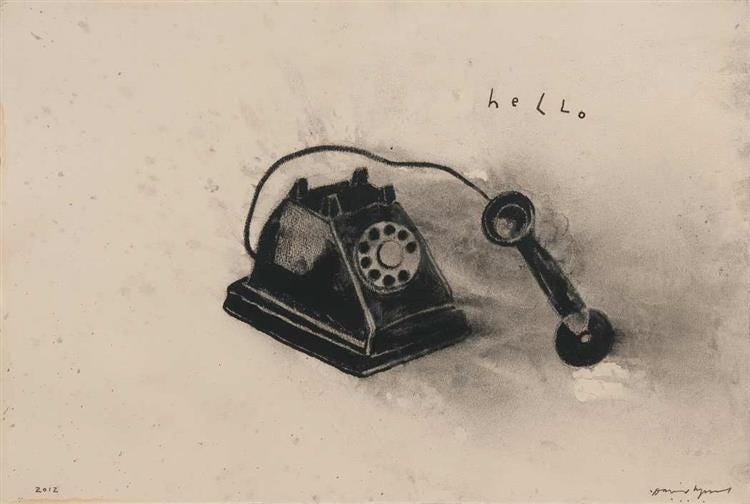

“I was thinking of Lynch a lot and particularly of how in Lynch, when you get all the way in, through that kind of labyrinth, you get to the inner chamber and there’s a control room. He always has a walkie-talkie or an intercom or CCTV going somewhere else. I think he gets that directly from Kafka. You get this always in Kafka, the room is never the room because it’s always just the antechamber to another room which is actually on a telephone to another room and even if you got to that other room that would just be the kind of back-up room.”

“Madison gets to the very heart of power, thinks it’s a place, and then discovers it’s a network. It’s just always a network, it’s never here. In the same way as U. notes that, in bed, she can’t come unless she’s thinking of someone else, power seems to operate the same way.”

“It’s about a staging of power, and a staging of power as a kind of perverse form of theatre. A theatre of repetition and simulation, of aesthetics done in an incredibly violent and exploitative way.”

I wonder about the ever-increasing processing power of technology and networks. What happens to us if we lose our seat as the writers of history, cede sovereignty to some future born A.I. and fall in line behind the Singularity?

“The whole Singularian thing seems rather Christian, frankly, it’s very teleological. One journalist called it ‘the rapture of the nerds’—it’s a good way of summing it up. In Satin Island, U. is meant to be writing the book, the über-book, the Great Report, and at one point he thinks that it’s impossible to write it. Then he has an even more horrific thought, which is that it’s already been written, but by software. Our networks of kinship are being mapped. Every time we go on Amazon, Facebook or just walk down the street it’s being written [down] by software and it’s only legible by software.”

“So at the same time U. is writing he’s slipping sideways. It’s kind of useless. The ultimately meaning is always eluding him. But at the same time there is this text produced, a set of agitations and connections that he is an agent in making, and I think they’re significant. He’s like Theseus, wandering blindly around a labyrinth but he has this ball of string, and he is mapping it.”

“As I said to Nicolas [Bourriaud] when we did our dialogue in Venice, the distinction isn’t between the human and the machine, but between the master script and the re-write. To come back to Burroughs, to Operation Re-write. The master script has already been written; the techno-corporate system is writing that. It’s always been written since the beginning, but the writer’s role isn’t really to write that, it’s to somehow get into that labyrinth and start unpicking and deterritorialising and recombining. That’s a machinic procedure in a way, a technology, but it’s an important one and one I’d see as being the technology of writing, of being a writer.”

*

Sometime after this. On the call. I forget exactly when as I’ve played the recording backwards and forwards too many times. It’s all cut ups of transcript and shuffled moments now. I ask about the INS, and whether the group is still active?

“Yeah, it’s a sleeper, an eternal sleeper,” T. replies. “Every so often we can do something and then maybe for eight months we won’t really do anything, but hopefully it’s still doing something even when we’re not doing anything.”

Actively inactive as it were.

“Actively inactive. Yeah, just waiting to be recalled.”

*Buy Satin Island by Tom McCarthy from your local independent bookstore ;)