Enter the Bauhauroque

Twenty years ago today I met artist Paul Laffoley, on the occasion of his 69th birthday, at a weekend at the Omega Institute in upstate New York, organised by Disinfo's Richard Metzger

To mark the anniversary, and what would have been his 89th birthday, I am sharing a short essay I wrote for the first issue of Under/current, published back in September 20081.

That day, Laffoley gave an almost three hour slide-show presentation of his work. As might be evident in what follows, it was, and in some significant ways still is, mind blowing to me. The collective experience across that entire weekend went a long way to inspiring my own transdisciplinary academic studies at the London Consortium2. During which, as a minor research skills training assignment the following autumn, I conducted my first ever interview — with Paul Laffoley! It took me almost four years to digest and unpick what the late, great visionary artist had shared with me. Even then, I was barely scratching the surface. Revisiting these events, and a cross-country road trip to visit Richard Metzger in Los Angeles and encounter Thanaton III for myself sandwiched in between them, has inspired a new and ambitious research project — one that I hope to share further details on with you in the near future. Infinite Thought will in part serve to document various aspects of that research, essays, notes, early drafts, interviews, inspirations, book reviews, revelations, thoughts, observations and the like generated throughout that journey.

***

Encountering US artist Paul Laffoley for the first time at a Disinformation weekend in upstate New York back in 2004 has left an indelible mark on me ever since. Somewhere between Buddha and Back to The Future’s Doc Brown, Laffoley gave a slide show of his works, lecturing with a lion’s paw in place of his left foot on his various theoretical subjects encompassing alternative histories, blue-prints for future human development, Goethe’s Ur-plant re-articulated into genetically engineered living architecture and his design for a working time machine. As collector Norman Dolph puts it in his foreword to Laffoley’s book The Phenomenolgy of Revelation, Laffoley could be the ‘spokes-painter of a consciousness yet unborn’.

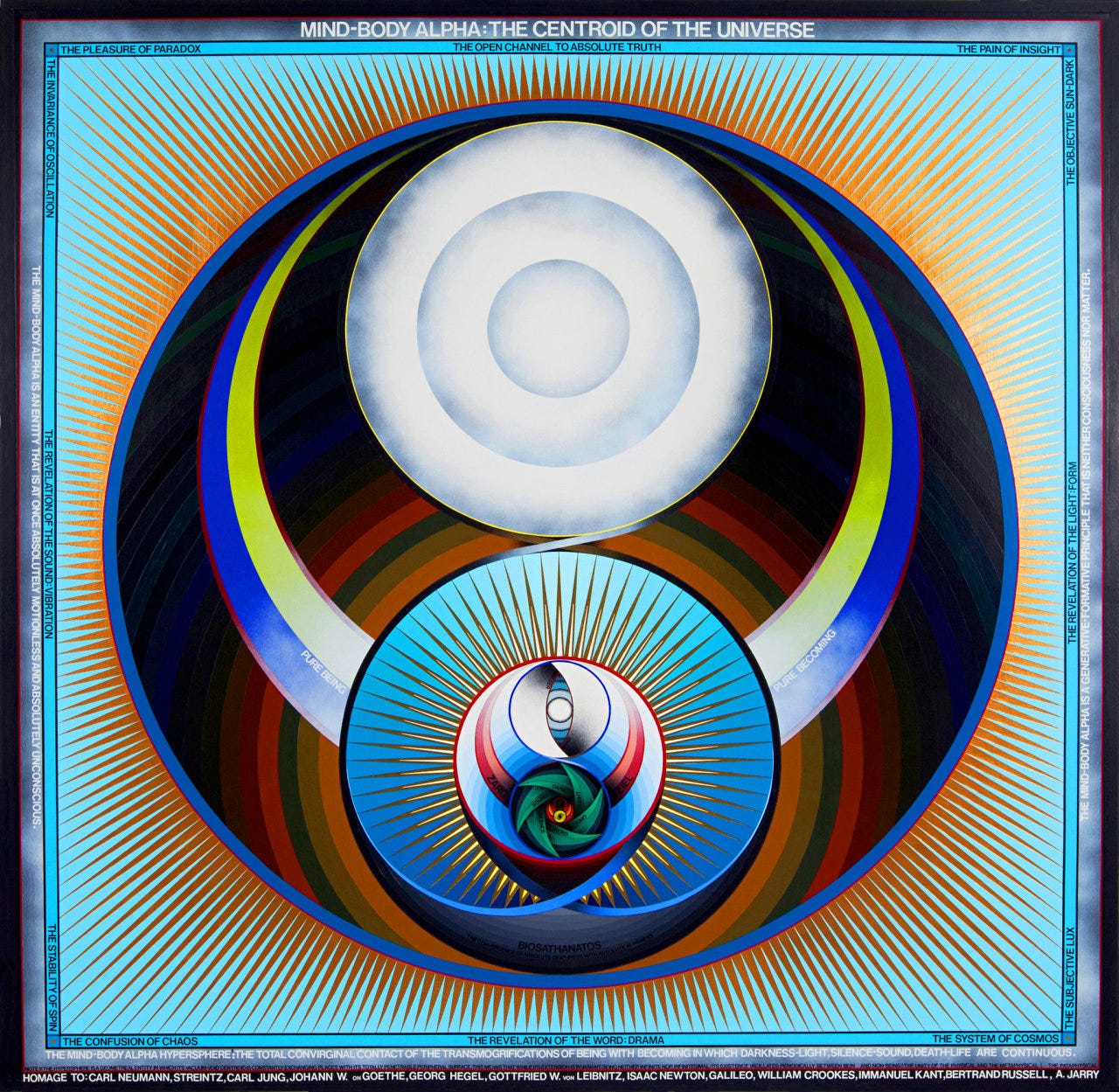

The problem is that the ideas presented in Laffoley’s science fiction visions are so far removed from established reality that by definition they’re insane. His mandalic architectural blueprints of metaphysical ideas regularly pay homage to and draw on such a diverse range of intellectual ingredients that no one person can possibly be capable of properly evaluating it all: Plato, Goethe, Schopenhauer, Madame Blavatsky, P.D. Ouspensky, Nikola Tesla, H.G Wells, Claude Bragdon, R. Buckminster-Fuller and Teilard de Chardin, to name a very small and under-representative selection. Much of Laffoley’s lack of attention within the mainstream art industry can be put down to this. As Disinformation host Richard Metzger muses, Laffoley’s ‘singular erudition’ and transdisciplinary auto-didacticism, almost entirely self-taught and thus free of academic compartmentalisation and categorisation, is so over most people’s heads that he’s misunderstood to the point of tragicomedy.

Despite this pervading incomprehensibility, Laffoley’s credentials are kookishly ivy-league impeccable. Educated in Classics and Art History at Brown, he went on to study under the authentic Modernists then teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he was dismissed for ‘conceptual deviancy’ — for proposing a living architecture of grafted and cultivated vegetable chimera as the only logical solution to the issue of low cost housing. He went on to work in the design group for the World Trade Centre at Emery Roth & Sons before apprenticing with visionary architect Fredrick Kiesler and Andy Warhol. His first solo show, in New York City, resulted in the gallery owner appropriating all Laffoley’s works and transposing them to a pot-smoked and hay strewn tent at the Woodstock festival, leaving Laffoley to commandeer a van and drive endlessly round the festival attempting to liberate them. Forming the one-man think-tank Boston Visionary Cell in 1971, Laffoley has dedicated his life to the practice of his singular form of art and philosophy, participating in over two hundred exhibitions both national and international.

Whilst staying at Warhol’s pre-Factory studio on Lexington Avenue in Harlem, an enormous abandoned fire station conversion, Laffoley was tasked with watching a wall of televisions running night and day like in the Bowie film The Man Who Fell to Earth. As the new guy he got the worst spots, from two in the morning until dawn. All that was broadcast at that time in those days was a series of test patterns. Laffoley thought these test patterns “looked pretty much like Tibetan mandalas” and compared them to Warhol’s own screen print multiples as in the Campbell’s Soup Cans: “once you set up diagonals, circles, put in multiple images you have Tanka or Tibetan religious paintings”. Warhol completely rejected this connection between religious metaphysical imagery and post-modern representations of our iterated cultural landscape in relation to his own work, but this offers us an essential clue in attempting to understand what Laffoley’s work could mean for us today.

Laffoley’s gallerist, Douglas Walla of Kent Fine Art, New York, uses the metaphor of operating systems to describe his work. Whilst Laffoley’s near autistic totalising world view could be misunderstood as outsider art, Walla contends that it is actually the very pinnacle of conceptual art. The constantly running televisions enabled Warhol to see what was filling the mass overmind – the contents of the zeitgeist’s self-image – which he could then take as the contents for his own Pop Art. The test patterns however concerned not the contents but the structure of this collective self-presentation via television; they were used to tune your set to pick up the broadcast image. Laffoley’s ‘operating systems’ could be thought of in the same way, as test images for attuning our mental software to a new frequency.

This notion of existential software or metaphysical cartography is perhaps most apparent in works such as Dimensionality or The Parturient Blessed Morality of Physiological Dimensionality where Laffoley proposes a theory of dimensionality at once divergent from not only our immediate experience and mundane ideas but also ground-breaking scientific research. Laffoley’s rejects the multi-dimensional String Theory of physicists such as Brian Greene or Lisa Randal as “like looking through a gigantic cosmic filing system”. For Laffoley scientific theories of dimensionality fail to get “a sense of what its like to be alive in there”, and fail to think temporality fully – in terms of possibility, manifestation and types of energy – and hence get stuck with the single catch-all word ‘time’.

Laffoley illustrates ‘Hyparxis’, the sixth dimension, through the role that anticipation plays in conversation. Anticipating the meaning that the other person is attempting to communicate to you determines their actuality, which of the possible manifestations or courses of the conversation become real; “completing possible manifestations for another person… you recognise you are both on the same page as the cliché goes”. Hyparxis or “the completion of being” involves the actualisation of every possibility, or an infinite number of compresent universes all on top of each other and collectively manifesting every possible configuration of being.

An essential aspect to Laffoley’s project is the challenge that these higher-dimensions pose and whether we can coherently think about them. As Laffoley points out, the consciousness living within this realm would be as different from us as our own is to that of an amoeba doing the back-stroke in a Petri dish. As the example of our limited conceptualisation of temporality shows, for Laffoley, “we have no nomenclature, I am trying to build a nomenclature to describe this because it explores possibilities and manifestations”. In effect, Laffoley’s work offers us potential cartographies of reality and the logics underpinning it on a far vaster scale than anything else we’re used to; a change of perspective capable of changing we way we live.

Perhaps Laffoley’s most famous painting is Thanaton III. In contrast to most of his other work, blueprints for unmade devices or metaphysical cartographies, Thanaton III is the machine itself. Laffoley describes it as a psychotronic device, meaning that the very structure and composition of the image utilises the activity of looking at it on the part of the viewer to impart knowledge to them. In order to understand this we need to turn to Laffoley’s theory of the epistemic ladder. Briefly, Laffoley sees a hierarchy in the mutually interdependent relation between the subject and object of knowledge in terms of which is active and which is passive. On the lowest rung of the ladder, that of the sign, “the knower is in control and that which is known is completely controlled”; the knower is active in relation to a completely passive object. As we move up the rungs the relationship balances out and then inverts, until we get to the symbol where “the knower is passive and the knowledge is active, you reach a point where a single occasion of knowing could not be wilfully released by you. In the true symbol, the environment has nothing to do with it at all. The knowledge is intransigent. You’re in rapture and you have to be pulled out of the epistemic structure by an environmental entity. That’s the way you could describe the knowingness of a mystical experience”.

Thanaton III invokes this symbolic potency through a deceptively simple optical technique. Standing about an inch away from painting with your hands touching it on the pads, you stare into the eye embedded into the great pyramid. That close to the canvas your eyes cross. Unable to sustain this, they defocus and wander outwards before refocusing back onto the black sphere in front of you. Each time your eyes de- then re-focus they effectively and unconsciously suck in more and more of the information coded both geometrically and textually into the surrounding imagery. After a while you stop seeing the image before you at all and start what could be called daydreaming. However, it’s a ‘daydream’ encoded and structured by Laffoley; the viewer is passively consuming the informational matrix actively provided by the image. Laffoley likens this to medieval illumination: “where you look at something that bypasses your conscious critical powers, and you have to absorb the ideas”. For Laffoley this image ‘downloads’ the information into the viewer through by-passing their standard routes of cognitive consumption and digestion.

Laffoley’s short-circuiting of disciplines and theories means that it’s almost impossible to think of his work in terms of the standard discourses and narratives of art history. His own typically divergent view of art history centres on the three phases of modernism: Heroic Modernism proper, post-modernism, and what he calls the ‘Bauhauroque’. For Laffoley, post-modernism began with the demolition of the Igoe-Pruitt housing project in 1972. The multi-award winning project crystallised modernist utopic visions in its attempt to solve the housing crisis but “exploded in their faces because no one could stay there”. Its demolition in turn crystallised the inherent flaws and failures of the modernist project itself. The Bauhauroque, “combining the heroic Modernism of the German Bauhaus, with its aspiration towards technical Utopia, and the exalted theatricality of the Italian Baroque, in which an exuberance of form and illusion serve to express the mystical union of art and life”, in turn was inaugurated by the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the demolition of the twin towers. Whilst Heroic Modernism penetrated the sublime barrier characterising Romanticism – incorporating the sublimity of confrontation with the absolute and the phenomenology of eternity into consciousness – we now face the kitsch barrier and the connected aesthetic of zombies, or the relation of thought to the undead. Loose comparisons could be made with Slavoj Žižek's engagements with the psychoanalytic undead of the lamella; or the immortality of the subject to an eternal truth for Alain Badiou. Through post-modernism, for Laffoley, the kitsch took over and became ubiquitous. The Bauhauroque and “zombie aesthetics [are] the attempt to penetrate the kitsch barrier. Kitsch is the visual equivalent of a zombie, because it is a reanimated form of life, like losing your soul and then repossessing your body with the same soul. You have to get past that and you have to recognize what it is that you are getting past, because otherwise you end up just repeating yourself, like people who don’t understand history are doomed to repeat it”.

Laffoley gives examples of cultural figures who seem to lack the ingredient of consciousness, behaving like un-conscious automatons – such as Elvis in the year before his death, the current state of Michael Jackson or ‘the culturally ubiquitous Andy Warhol for his whole life’ – to explain how zombie aesthetics operates: they “exaggerate positions so that people can observe that in a way that’s never been done before and that opens up possibilities for people. The function that people who indulge in zombie aesthetics perform is that they give you an inoculation, like getting inoculated with a dead virus because these people are working with death themselves. Like recognising there is a portal to something new, they are creative road signs to the future”. Laffoley likens this inoculation to the effect that Jules Verne’s Man on the Moon had in relation to the Apollo landings. Verne got the sensibility of going to the moon so spot on that when it actually happened the actual surprise had been muted to the point that some people believed it wasn’t real: “the shock of the new was over”. That Laffoley can easily be equated with outsider art comes from the kitsch nature of his images: “all outsider art is pure kitsch, done without any satiric content and just living in it completely. That is what in essence ends with the Bauhauroque”.

The ‘operation’ of Thanaton III – a touchstone for Laffoley’s entire body of work and a distillation of his theories – could thus be seen as purporting to put one into the state of a zombie, rendered totally passive by the inversion of the epistemic relation between the knower and that which is known, and hence penetrating the kitsch barrier. Interestingly Laffoley suggest that the same symptoms can be produced by an overexposure to visual kitsch in the ‘worlds of bad taste’ such as Las Vegas, Times Square, Graceland, Disneyland and the entire of Switzerland (Botox also produces the visual symptoms of undead zombie-ness, if only on the surface).

Laffoley makes an art form of metaphysical and conceptual speculation, continually pitching us into unbelievable worlds, pushing our incredulity and testing our abilities to think of reality in radically different ways like an instructor of transcendental yoga. He believes true science fiction died in 1955 with Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land and that after that the genre “became ad hoc research and development for companies” – think the communicator from Star Trek and the mobile phone in your pocket. In this sense, we could see Laffoley’s ‘fictions’ as mapping out the radical contours or terrain of the scene of our future thought and consciousness. He believes that all knowledge is a mix of the physical and the metaphysical; conceiving the world in terms of spirit, matter or the opposition of the two is incorrect – rather “there are degrees of characteristics from one to the other”, and whilst our analogies and grasps at conceiving the world inherently fail, “each time it leaves in its wake a nomenclature that gives you the memory of having come up against a problem and from which you can eventually forge on”.

For more information visit https://paullaffoley.net/

**

To anyone interested in hearing more about the wider research project, do reach out. Am happy to chat and share ideas.

If anyone is interested in print, I do have a few hard copies of the issue available. DMs open.

As well as the concept and youthful audacity to launch Under/current itself, with my good friends and colleagues at the time.